Confederate Whitworth Sharpshooters

I became interested in the Whitworth rifle used by Confederate Sharpshooters and after doing some research, decided to write a short article about what I’ve discovered

The battalion sharpshooters were essentially “light infantry” comparable to

Berdan Sharpshooters, only fewer in number. They served as pickets, scouts, and

advanced skirmishers. Often, they were handpicked men.

The Whitworth and Kerr-armed men were not called “snipers”, they were just

referred to as “Sharpshooters.”

According to the U.S. Army sniper training manual (TC23-l4, Sniper Training and

Employment) the word “sniper” originated in the last century with the British

Army in India where the snipe was a favorite game fowl. A good snipe hunter had

to be an expert shot and know his quarry’s habits.

The Kerr rifle required a special long cylindrical lead bullet, wrapped in paper with a special small-bore rifle powder made in England. British-made cartridges were not easy for the Confederacy to obtain through the Union naval blockade. Even though Kerr rifles were quite accurate at long ranges (1000 yards), they had a fairly high trajectory compared to modern sniper rifles, accurate long range fire required accurate estimation of the range to the target. This could be accomplished by using a stadia, a small hand-held instrument that allowed the shooter to estimate range based on the visual size of a target. These were rarely available, practicing range estimation was the primary training for long range shooting.

In 1860 a company known as the Whitworth Rifle Company was established in

Manchester, England. In May 1862, the firm’s name was changed to the Manchester

Ordnance & Rifle Company, because by then Whitworth had begun producing cannons.

Most rifles were made in .451 caliber and rifled with a 20-inch pitch, but there

are very rare versions with a .564 bore and a 25-inch spiral. The earliest

military Whitworths manufactured in any numbers were those with 39-inch barrels

made for government trials conducted in 1857 and 1858. In 1860 a small number of

two military models, a heavy and a light-barreled version, were prepared at

Enfield and rifled at Manchester. Testing showed superior characteristics and

led the British government to order the production at Enfield in 1862 of 1,000

Whitworths with 36-inch iron barrels. The 1862 Whitworth version was so

successful, another 7,900 rifles, known as “short” Whitworths with 33-inch steel

barrels, were manufactured at Enfield in 1863. During this time, 100 similar

rifles were made by Whitworth at the Manchester Company’s works. These became

known as “Manchester” Whitworths.

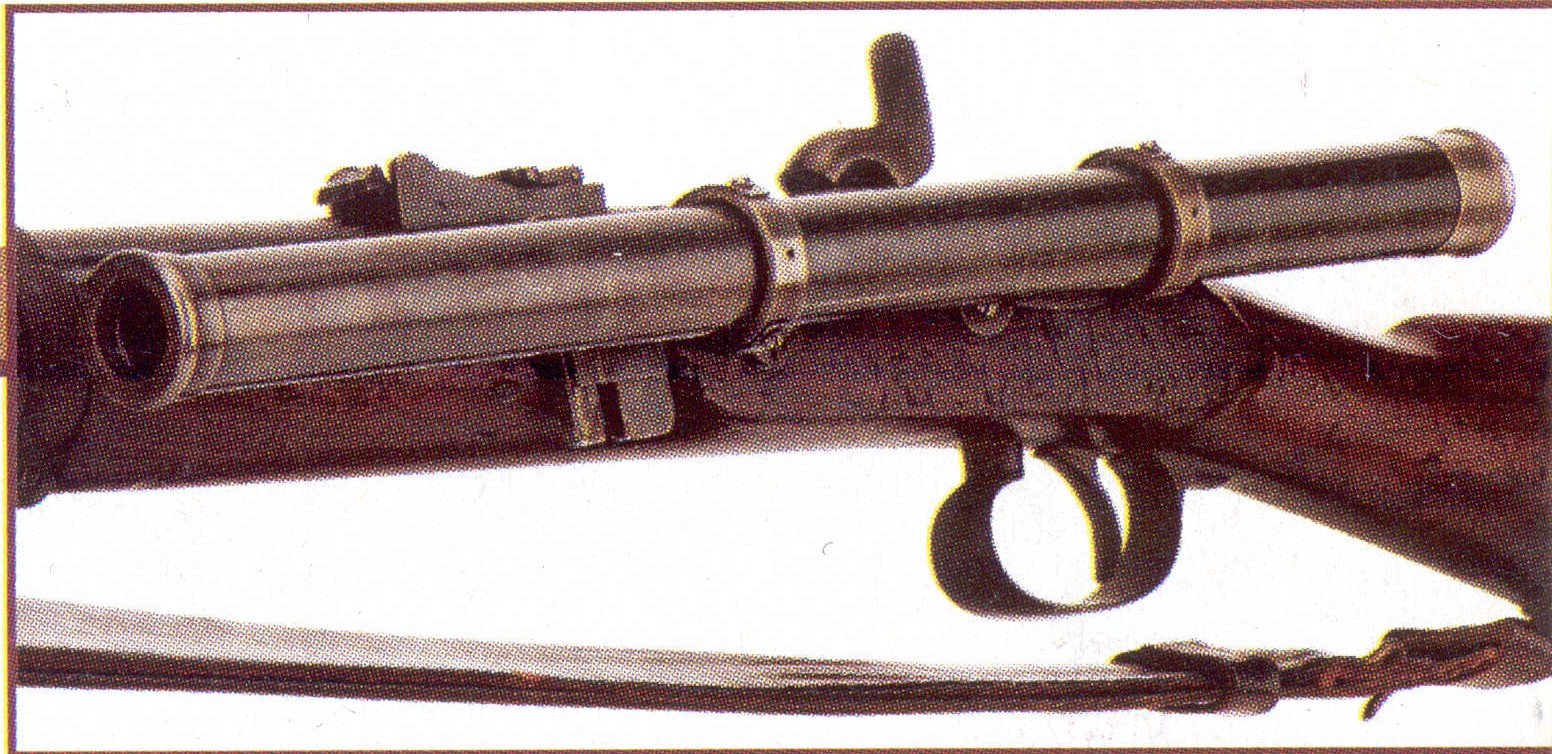

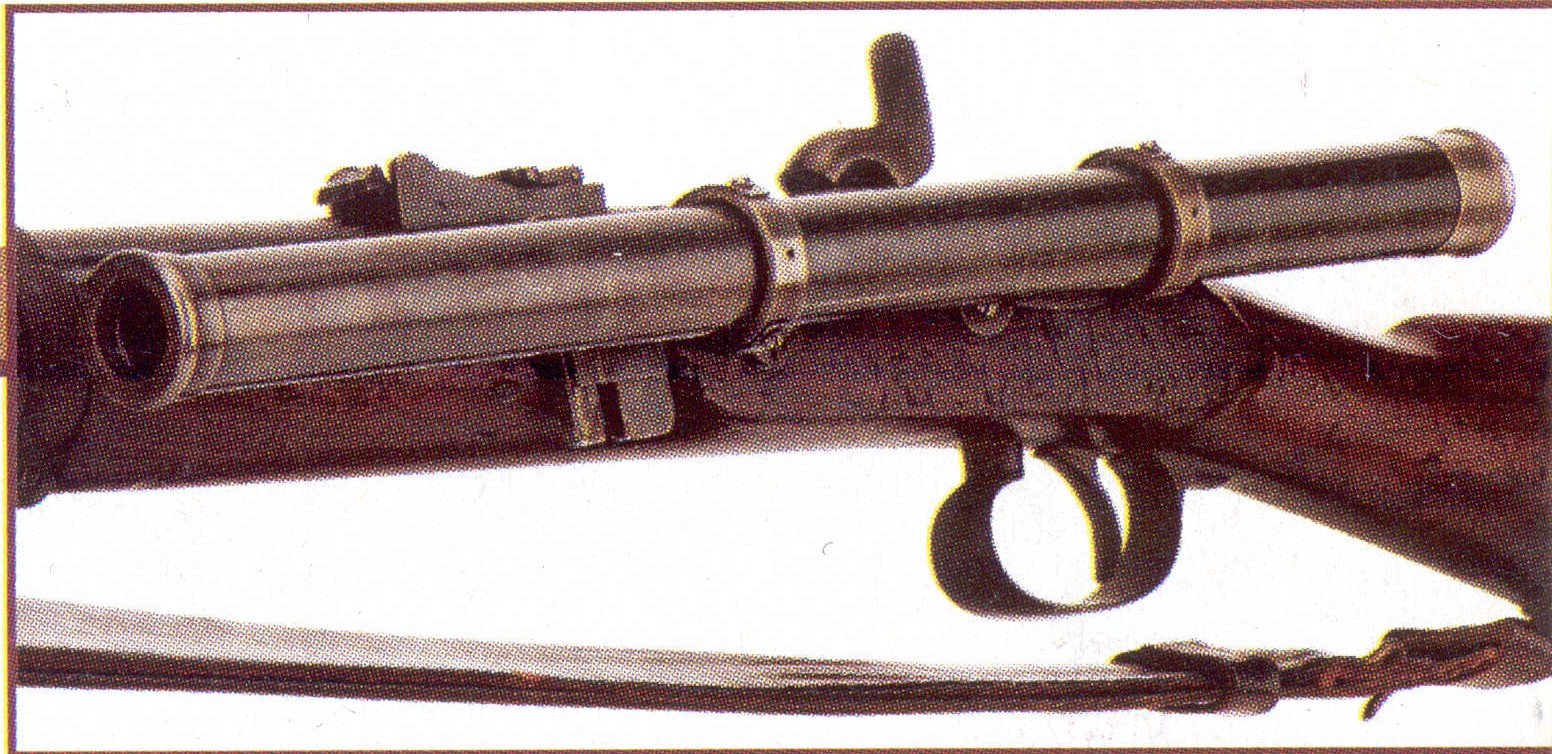

The manufacturing process of the Whitworth was very unique. The barrel was cast

into a bar from molten steel and compressed while in a fluid state. The

compression set up internal stresses that allowed the barrel to accept very

powerful loads. The Whitworth was extremely well made, with iron mountings

throughout and an attachment for a telescopic sight mounted on the left side. It

had iron sights graduated to 1200 yards. With a Davidson scope attached it was

accurate up to 1800 yards.

The

Whitworth bore was hexagonal in shape to increase accuracy; a hexagon bullet was

the most accurate. But most Confederates used cylindrical bullets probably due

to supply reasons and because after several shots it became very difficult to

ram a hexagon bullet down the barrel.

General

Specifications of the Whitworth Rifle, Ammunition and Telescopic Sight

Caliber:

.45 (.451, rifled, six-sided, or hexagonal)

Bore:

.450 inches; one turn in twenty inches

Barrel Length:

thirty-three inches, thirty-six, and thirty-nine inches

Rifling:

hexagonal (six grooves, slight rounding at the corners)

Total Rifle Length:

forty-nine inches (some noted at fifty-five inches)

Weight:

(without scope) eight pounds, fifteen ounces (8.95lbs.)

Scope:

(mounted left side) Davidson telescope, fourteen and one-half inches

length,

cross-wire reticule; 145/8” x 15/16”.

Some Whitworth rifles were reported with a “Globe”

sight instead of a telescopic

sight.

An early account of a Whitworth Sharpshooter was written by a surviving

Sharpshooter following the war.

John

West was a Georgian in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Below is an excerpt from

his writings.

“In ‘62 General Lee received thirteen

fine English Whitworth rifles that were warranted to eighteen hundred yards.

These were the best guns in the service on either side. Thirteen of the best

marksmen in the army were detailed for this special service, and I was the only

Georgian that was selected. We were placed under the command General Brown, who

had no other duty than to command us. We were practiced three months before

going into service. A score of every shot was kept during these three months,

and at the end I was 176 shots in the bulls eye ahead of the rest. The last day

of practice in marksmanship was tested by our superior officers. A white board

two feet square with black diamond about the size of an egg in the center was

placed fifteen hundred yards away. The wind was very chilly and it was

unfavorable for good shooting, and I put three bullets in the diamond and seven

in the white of the board. I beat the record and won the choice of horse,

bridle, spurs, gun, revolvers, and sabre. Our accouterments were the best the

army could afford. Then we entered active service, and I have been through

scenes which have tried men’s souls. I soon became indifferent to danger and

inured to hardships and privations. I have killed men from ten paces distance to

a mile. I have no idea how many I killed but I made a good many bite the dust.

We were sometimes employed separately and collectively; sometimes

scouting, then sharpshooting. Our most effective work was in picking off the

officers, silencing batteries and protecting our lines from the enemies

Sharpshooters. Artillerymen could

stand anything better than they could sharpshooting, and they would turn their

guns upon a Sharpshooter as quick as they would upon a battery. You see, we

could pick off their gunners so easily. Myself and a comrade completely silenced

a battery of six guns in less than two hours on one occasion. The battery was

then stormed and captured. I heard General Lee say he would rather have those

thirteen sharpshooters than any regiment in the army. We frequently resorted to

various artifices in our warfare. Sometimes we would climb a tree and pin leaves

all over our clothes to keep their color from betraying us. When two of us would

be together and a Yankee Sharpshooter would be trying to get a shot at us, one

of us would put his hat on a ramrod and poke it up from behind the object that

concealed and protected us, and when the Yankee showed his head to shoot at the

hat, the other one would put a bullet through his head. I have shot them out of

trees and seen them fall like coons. When we were in grass or grain we would

fire and fall over and roll several yards from the spot whence we fired and the

Yankee sharpshooters would fire away at the smoke.”

The Confederate Whitworth Sharpshooters claimed they killed many Yankee Sharpshooters and didn’t seem to hold Berdan’s in very high regard. It seems they resented all the attention the Berdan’s were getting in the northern press and claimed that Yankee Sharpshooters killed very few Whitworth men and were not as “good shots” as they were.